Very psyched to be back on here announcing that Zulu P is releasing their 2nd mixtape (produced by Ben Malkin of Goodbye Better). Â Tey got a third slated, so I’ll be back with that soon, but for now, get into this. Â And if you’re a grimey homie, go straight to track two, ‘I’m Up On These Streets 69’, fierce vibes.

AdHoc interviews Sam Hillmer:

Zulu P is a rap group comprised of developmentally disabled adults. Sam Hillmer views his involvement with Zulu P– an combination of promotion, spokesmanship, and managing– as cooler than anything he’s done in the experimental music scene. This may come as a surprise to any fans of his persistently forward-thinking free music project Zs, a stalwart of the experimental scene of this century that has included such shredders as Greg Fox, Ben Greenberg, and Patrick Higgins. But it’s not a shocking statement, considering his past involvement with the 9/11 Thesaurus project, in which he helped produce albums for a rap group of at-risk North Brooklyn teenagers.

Hillmer got in touch with me back in early November about posting Zulu P’s most recent mixtape, and I had a hard time figuring out how to present it. Forget the fact that Ad Hoc barely posts rap– it felt as if many would view this Nas and Wu Tang Clan-influenced mixtape as an oddity, as a presentation of possibly-exploitatve outsider art. After all, that is how a good deal of music fans discuss better-known disabled artists, like Wesley Willis, or Daniel Johnston, or The Goddess Bunny. The most logical solution ended up being to have a chat with Hillmer himself about his involvement with Zulu P, and ultimately his greater social project as a Brooklyn resident.

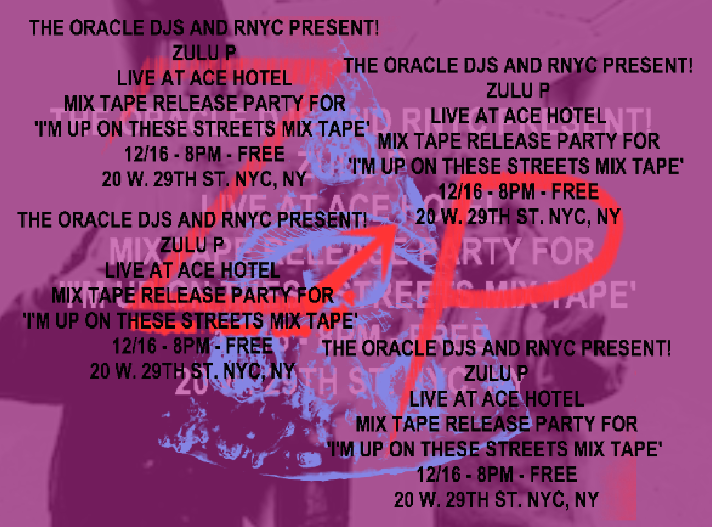

His work with Representing NYC is the embodiment of this project, one of uniting disparate communities that live in such close proximity to one another– often just blocks away– in the name of improving the area, and in turn world, those groups inhabit. It should be of little surprise that the implications of the Zulu P mixtape extend past the mission of giving a group of developmentally disabled adults an outlet for their art. You can catch the group perform next Monday, December 16th, at the ACE Hotel in Manhattan.

Ad Hoc: How did you get involved with Zulu P? Given your prior work with 9/11 Thesaurus, it would seem that you have some broader social mission to bridge the different worlds within Brooklyn.

Sam Hillmer: I first met Zulu P working with Carnegie Hall, of all organizations, doing some community projects with different social service organizations on Carnegie Hall’s behalf. The organization that works with Zulu P was one of the organizations I worked with. I was leading a project where we were producing a concert in one of their centers, and essentially what we did was round up all of the musicians who were working in their centers and get them to do this collaboration with Carnegie Hall to produce a concert. In the context of that collaboration, I hit it off with some of the staff there, and also met Zulu P, and another group called the Five Lovers, and I just kind of dog-eared it because I knew I really vibed with some of the folks working there and that they would be amenable to a collaboration with my project Representing NYC, and I knew I really wanted to work with them. That was three years ago. We just stayed in touch, and finally the stars aligned, and they were able to get me in here, and I had the time, so we made it happen. So I just showed up, but Zulu P have been a band for a number of years now. Three-ish years, I think. I kind of came in to take their existing recordings and try and build greater awareness around them and to make some new recordings.

AH: When you say greater awareness, who are you looking to make aware?

SH: I didn’t address the piece of your question about the social mission and whatnot. I mean, in my own music process, and in the work that I do to support other people’s work, I am not a stickler about where awareness and attention comes from. From my point of view, if you’re making music– especially music that has within it some type of progressive social agenda or philosophical or aesthetic thing where you’re challenging the public’s perception of something– as far as I’m concerned, the more you hear it, the more you’re doing your job. It’s about being in front of anybody who’s down. It’s not about who [you are in front of] specifically, per se. So talking to Ad Hoc is awesome, but I think [talking to] the New Yorker and the Daily News is awesome, too.

AH: It is very much a New York story. It’s not just a simple musical phenomenon. It concerns the lives of people who live here, a group you didn’t hear about too often. So could you talk a little more about the social element?

SH: Something that I’m very committed to is the notion that people who fall under some category or other– at risk youth, developmentally disabled people, hurricane sandy victims, it could be anything– be directly involved in the way the narratives about them are conveyed. Because when it comes to these populations, a lot of the ways that people build awareness about them is through this kind of reductive statistical filter presented in a journalistic fashion through outlets like The New York Times or NPR you know? And from my point of view, the most important thing is that the actual individuals in question are the ones delivering the narratives. In this case I am being interviewed about this work, but it’s my collaborators in Zulu P on the tracks and at the shows. And one of the meanings of being a representative of these voices is supporting them in articulating what’s happening in their lives, and creating opportunities for them to broadcast about that to people that aren’t in their situation. In the DIY community, we’re uniquely situated to do this work, but it is very seldom done. We are a concentration of people who have a type of political-social bent, as well as the economic and cultural wealth needed to make these kinds of projects happen. So the social mission is two-fold: to create the opportunities for the participants, as well as to advocate within our own community that this type of work be done and valued by us.

AH: It seems to me that a lot of the work you’re doing is bridging neighboring communities that barely interact. How could such a border be broken down between these two communities that coexist but don’t engage in a meaningful, artistic way?

SH: That is a difficult question with a complicated answer, and certainly more than one answer. I can highlight certain strategies. One of the strategies of Representing NYC is to create value inside the DIY or indie community around the kind of work that brings people into the kinds of dialogue Representing NYC fosters. Think of it this way: if you’re out at a show, you’re out at a bar, you’re meeting people, you might say, “What do you do?” And people are like “I’m an art handler, I write for Spin magazine, I tend bar at Daddy’s,” what have you– these things have some sort of social caché on our scene. But if they were to say, “I’m a social worker, I’m a speech therapist”– ehh, not so much social caché in terms of the scene right? Instead it’s like, “Yeah, okay, cool, respect, you have a regular job, but that job is not part of the scene.” What Representing NYC is trying to do is say that those callings and vocations can be part of the DIY/indie scene– it is related to the scene, and it should be. You’re on the scene when you’re at work, not just when you’re playing with your band or at your art opening or whatever. And in this way, you are opening doors for a broad array of people to our social milieu. If we don’t succeed at doing this, our scene will remain pretty exclusive socio-economically.

By the way, you see this kind of work starting to happen with a lot of the DIY venues that moved to Bushwick, like Silent Barn, Secret Project Robot, Market Hotel, which I’m a part of. All of these folks are actually taking on this type of agenda, and it seems that we are starting to value this in our social context. Beyond that, there’s a whole other set of strategies that I could get into about the boundaries that exist on the side of the social services practice and the communities that dwell there, but that may be a bit outside the scope of this article.

AH: If you want to go into it, I wouldn’t mind hearing it.

SH: Sure. [While] working inside a social services organizations that tries to create the types of opportunities that lead to folks and groups like Zulu P and 9/11 Thesaurus having visibility outside the social services apparatus, there is a labyrinth of red tape that you would not believe. It’s very, very, very demanding, and often not very rewarding to negotiate. First of all, you have to convince people that this matters. It’s like, why does it even matter if Ad Hoc or Noisey posts about Zulu P? Who cares? In the world of social services, Ad Hoc and Noisey don’t exist, so first of all, you have to make the case that this matters. And then when you do find really good partners who want to support the work, there are still incredible headaches– to make sure that when it does pop off, it doesn’t offend someone or cross a boundary it’s not supposed to cross.

And then, you’ve got the communities themselves. In the case of the folks from Zulu P, it’s a bit more diffuse because its not a geographic community, it’s a community constituted by a biological, psychological make-up. In the community that I was working with with 9/11 Thesaurus, you’re talking about geographic, socio-economic, social, cultural, you know– actual communities. I can talk briefly about working in Brownsville, Bed Stuy, Bushwick, in the indigenous, if you will, communities there. I could write a book about this, but what comes to mind immediately is the incredible amount of skepticism and lack of trust you encounter.

AH: From which side?

SH: The participants.

AH: Sure, the whole idea of “Am I being exploited? Who are these people?â€

SH: So you get the idea of that–and a very well-founded idea. If anybody researched this, they’d have tons of evidence that they very well might be exploited. So it’s an uphill battle, and it’s one that has to be fought. And the way that you fight is you build relationships. Most people, I knew them– I knew their mothers, their fathers, their aunts, their uncles their social workers, their case workers, you name it. I had all those people on speed dial. It was deep. It was not like they had a record and I helped put it out. It took me three years to make progress on the 9/11 Thesaurus project. So addressing the lack of trust and skepticism through extensive relationship building, which is a long and arduous process, and also a very rewarding process, is integral to opening those lines of communication.

AH: This is why it seems to be important for you to talk about. There is skepticism on the listeners’ end as well. If we put it on the site, readers wonder, “Oh, what’s this? Why should I care?â€

SH: Sure. The specific goals of Representing NYC are manifold: to create the opportunities for the individuals, but it’s also to promote the conversation in our community as well. It’s not charity. The one percent thing is real. The growing disparity of resources between people who are born on the poverty line and the one or ten percent with resources– that’s real. It’s communities like ours, I think, that could be engaging in the project of wealth redistribution or the processes of wealth redistribution, as we are specifically geographically located in areas where that is most pertinent, and we specifically value inclusivity and egalitarian-ness. We’re the only the people who are going to to do this, and if we don’t, it will come back on all of us in a way that isn’t cool for anyone.